March welcomes springtime and is a time to celebrate women through time. Most notable are the many African American women who have cemented their place in history. History has introduced us to many historical figures, such as Harriet Tubman and the extraordinary ladies celebrated in the movie Hidden Figures with their exceptional contribution to mathematics for NASA. We also know Madame CJ Walker, one of the self-made female millionaires and, much more important African American women. There are ones in our community through history that we know very little about, yet their legacy is just as important as any other. Locally, their names are known and made their mark in history with the efforts to make sure African American history is not forgotten. Generations to come may or may not have come to know their stories. In actuality, theirs is one to be heard as it fits into the fabric of African American history.

One such story is in Las Vegas, NV, with a two-room schoolhouse built in 1923. Helen Stewart founded the Historic Westside School to educate the Paiute children from the Paiute community/reservation in Las Vegas. By 1948, the school added two more rooms to accommodate the many African American children of families who migrated to Las Vegas to escape racism, segregation, and a better life. Although the school was the only integrated school for the Paiutes, Hispanic, and poor white children, the school was mostly populated with African Americans.

Aside from Las Vegas, NV is famous for its lights and glamour along The Strip and is a popular tourist destination; the city also has a rich African American history. Back in the day, Las Vegas had its amount of racism and Jim Crow against African Americans, and it was often found. The citizens of African Americans made up a small community on the western side of town where they lived and owned businesses because the mayor wanted them secluded from the rest of the city. The Westside did thrive along with its own version of the strip, including the Moulin Rouge, the first integrated casino in the United States. That story, though, is for another blog entry. The Westside Community was mainly accessible through a tunnel called the Bonanza Underpass, pretty much concealed away from the glitz and glamour. African Americans on the Westside would use the underpass to get to work downtown and on the strip, and for the high school. Today, the underpass is a paved street nearby downtown Las Vegas that welcomes visitors to the historic area as it is now a historical landmark known as the Historical Westside.

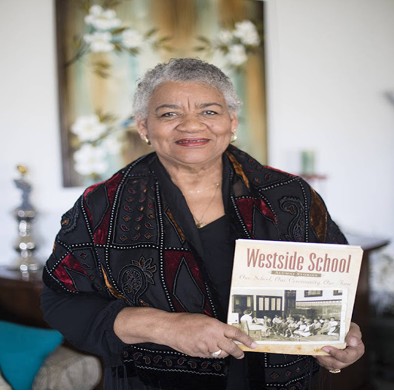

A local African American citizen, Brenda Williams, is an alumnus of the Historic Westside School located on the Westside. She has worked in making the school and Westside community historical landmarks. In addition, as president of the Westside School Alumni Foundation, she structured and published a book highlighting many of the school’s alums and their life in the community which proceeds fund scholarships and the preservation of Las Vegas’s Westside community.

After graduating the 8th grade and high school, Brenda became a prominent member of Las Vegas, NV. She was the first African American to work in a bank as a bank teller and the first non-custodial employee for the city and the State of Nevada. At the Westside Library, she generously donated books for children. Brenda has worked on the city council and is still very active today. Much of her community work is preserving African American history in Las Vegas, exclusively on the Westside. Along with making the Westside School a historical landmark, she has brought back to life the stories of many African American citizens of the Historic Westside community and Las Vegas. One such story is of Eleanor Sue Marks-Graves, an alumnus of the Westside School whose family came to Las Vegas from the south. She became a remembered pianist and community member.

The Marks family migrated to Las Vegas, NV, from Fordyce, Arkansas, in the early 1940s. Eleanor Sue was only four years old but vividly remembered living in a vast army-like tent when they first came, as many other families did in West Las Vegas. Her father got a job at the Basic Magnesium Plant, while her mother did much work volunteering for spiritual growth in the community. Finally, they could move into a house near the Westside school Eleanor attended when she was old enough.

Eleanor’s mother was also a piano teacher and gave her lessons. It was soon noticed that Eleanor had an exceptional talent for the piano and, at the age of 10, was sent to further study at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, Canada. However, she returned home, continued schooling at the Westside School, and furthered her piano instruction at the Fletcher Conservatory. When she graduated the 8th grade, she was honored with playing the piano for the graduation ceremony. She went on to Las Vegas High School, which was integrated but did not walk with her class at graduation because she lost her mother in death.

Eleanor became an important part of Las Vegas history with her piano talent as time went on. Many professional musicians sought after her to assist with their performances on the Las Vegas Strip, playing in several of the casinos. She collaborated with entertainers such as Ray Charles and Duke Ellington when he wrote the score for “Paris Blues.” She was also known to play the organ or piano inside the Moulin Rouge. In addition, she performed on cruise ships, invited to Washington, DC, and many more places.

Eleanor retired in Southern California and taught piano until her death in May 2021. She was well-loved and remembered in the Westside, Las Vegas, NV. As a tribute to her great-grandmother, her great grand-daughter, who also attended Las Vegas High School, attached a photo of Eleanor to her graduation gown so Eleanor could symbolically walk along with her as she walked during the senior class graduation ceremony. Eleanor and Brenda have become important figures as outstanding African American alums of the Historic Westside School.